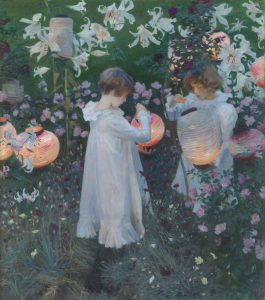

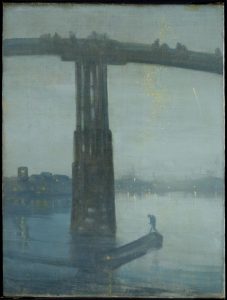

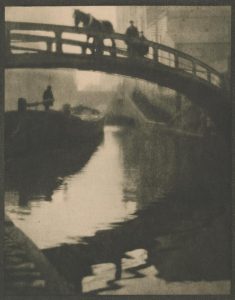

photos by Matteo Favero

The New York Photography Diary is pleased to host its inaugural exhibition, Elsewhere is a Negative Mirror, at Carmel by the Green in East London. This exhibition follows The Physical Fabric of Cities—organized by London Photography Diary—and is the second in a year-long program of shows being organized by The Photography Diaries. Elsewhere is a Negative Mirror is curated by New York Photography Diary editors Daniel Pateman and Will Fenstermaker . The head curator for this exhibition is Ivana D’Accico.

Inspired by the shock of Brexit in Britain and corresponding xenophobic, nativist tones in US and European politics, Elsewhere is a Negative Mirror features the work of eight international artists who responded to the set theme of Borders. Each photographer explores boundaries in the midst of a reconfiguration, provoking a reconciliation with the limits at which one defines identity, homeland, and ontological frameworks.

The exhibition title comes from a dialogue between the Venetian merchant Marco Polo and Mongol Emperor Kublai Khan in Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities (1972) and speaks to the way communities define themselves in opposition to other people. Polo, an exile—albeit a voluntary one—tells Kublai of a peculiar sensation: the recognition of oneself in the otherness of those who live beyond the border. Coming upon daily life within an unfamiliar city, Polo recounts that “the traveler finds again a past of his that he did not know he had: the foreignness of what you no longer are or no longer possess lies in wait for you in foreign, unpossessed places.”

To this, Kublai responds that travel brings one into contact with one’s past, one’s possible futures, and all the presents that could have been. “Elsewhere is a negative mirror,” Polo says. “The traveler recognizes the little that is his, discovering much he has not had and will never have.”

These photographs, like negative mirrors, show what is familiar in unfamiliar places. In them, one finds home in a world that has been divided into parts—conquered, nationalized, and quantified—its distinctions marked by thresholds that have only the illusion of inviolability.

“Elsewhere Is a Negative Mirror” will run from October 6th to December 13th, 2016 at Carmel by the Green, next to Bethnal Green tube station in East London. Please join us for our opening on October 6th from 6–9pm, or as part of Whitechapel’s First Thursdays in November.

Carmel by the Green

287A Cambridge Heath Road

London, E2 0EL

020 8616 5750

ARTISTS

Clement Valla

Clement Valla’s “Postcards from Google Earth” depict moments where Google’s two-dimensional imaging software has misaligned with the three-dimensional mapping software, marking a boundary between actual and representational nature. “These images are not glitches,” Valla says. “They are an edge condition… They reveal a new model of representation: not through indexical photographs but through automated data collection from a myriad of different sources constantly updated and endlessly combined to create a seamless illusion.”

Clement Valla (based in Brooklyn, NY) works with computer-based picture-producing apparatuses, and how they transform representation and ways of seeing. His work has been exhibited at XPO Gallery, Paris; Transfer Gallery, Brooklyn; The Indianapolis Museum of Art, Indianapolis; Museum of the Moving Image, New York; Thommassen Galleri, Gothenburg; Bitforms Gallery, New York; Mulherin + Pollard Projects, New York; DAAP Galleries, University of Cincinnati; 319 Scholes, New York; and the Villa Terrace Decorative Arts Museum, Milwaukee. His work has been cited in The Guardian, Wall Street Journal, TIME Magazine, El Pais, Huffington Post, Rhizome, Domus, Wired, The Brooklyn Rail, Liberation, and on BBC television.

Postcard from Google Earth (43°5’22.07″N, 79° 4’5.97″W), by Clement Valla

COLIN EDGINGTON

Colin Edgington’s work explores ash as a symbol of state changes, particularly of the boundary between the visible and the invisible, the living and the non-living. In this way, he says, “it epitomizes transience.” Drawn from his upbringing in the American southwest, the ash structures are built to resemble demarcations of place, and are ultimately destroyed after photographing.

Colin Edgington (based in Greater New York) is a visual artist and writer. His work has been exhibited internationally and published nationally. He was named the winner of the Iowa Review Photography Prize, judged by Alec Soth, for his seemingly authorless body of work titled [umbrae] in 2012. He holds a BAFA in studio art from the University of New Mexico, an MFA in studio art from the Mason Gross School of Arts, Rutgers University, and an MFA in Art Criticism & Writing from the School of Visual Arts, NYC.

Border Monument 1, by Colin Edgington

GRISELDA SAN MARTIN

Griselda San Martin’s series “The Wall” documents families separated by their immigration status, who gather to meet at Friendship Park, located along the border between San Diego, California and Tijuana, Mexico. What started out as a simple barbed wire fence in the 1970’s has been expanded into an imposing metal wall, which extends some three hundred feet into the ocean. On the American side, patrols runs the border, while in Mexico, families roam freely and eat at restaurants nearby. At the wall, families meet, whispering to each other between the stakes, poking their fingers through the stakes and steel mesh to touch their loved ones.

Griselda San Martin (based in New York, NY; Tijuana, Mexico; and Barcelona, Spain) is a documentary photographer and visual journalist. Her documentary work explores transborder and transnational issues and focuses on concepts of identity and belonging in diasporic communities and ethnic minorities. She has been photographing and documenting the U.S.-Mexico border for the past four years. In June, 2015 she graduated from the the Photojournalism and Documentary photography program at the International Center of Photography in New York.

Through the Wall, 2015, from “The Wall” by Griselda San Martin

NETTA LAUFER

Netta Laufer’s series “25FT” appropriates military surveillance footage of the wall separating Israel and Palestinian territories. By focusing the camera on animals along the border, she says, the series “focuses on, and examines, a fragmented and awed human reality, versus nature that seems to operate as a parallel universe, working its way around… our self- perception as a superior race overseeing and independent of nature’s ecosystem.” In depicting wildlife, the artist shows how manmade borders come into conflict with the unboundedness of nature. Animals passing through their natural migratory routes are stopped by the border, irrespective of their own dependance on the land that we share.

Netta Laufer (based in New York, NY) was born in Israel (1986), and raised in both Jerusalem and New York. Laufer’s “Black Beauty” was exhibited in a solo show at the Bloomfield Science Museum in Jerusalem (2013), and at Fresh Paint 7 art fair in Tel-Aviv (2015). Recently Laufer exhibited the work “Cells” at Alfred Gallery, Tel-Aviv (2016). Her latest work “25FT” granted her the SVA Alumni Society Scholarship (2016)

Dog, كلب, כלב, from “25FT” by Netta Laufer

JURAJ STAROVECKY

Juraj Starovecky presents a photographic recreation of Iron Curtain-era Czechoslovakia in his series “The Curtain”. While skillfully placing the contemporary viewer in the shoes of those who risked their lives to cross the state border, he also encourages us to remember the human outrages of recent history. “Over 866 people were killed while trying to cross the state border via the so called Iron Curtain between 1948 – 1989 in former Czechoslovakia. The purpose of this apparatus of absolute power was to kill and terrorize trespassers and to preserve fear inside an omnipotent political system, which had been denying basic human rights and freedom for 40 years. The contemporary status of social awareness about this significant problem of the past era is alarming. Instead of facing our own past and dealing with its traumas, collective amnesia is manifesting.” Starovecky’s triptych Untitled (Alert) depicts the sort of warning signal deployed by guards to help apprehend trespassers, and places the viewer within a visceral dynamic of hunter vs. hunted.

Juraj Starovecky (based in Bratislava, Slovakia) works as freelance photographer. He finished his MFA at the Academy of Fine Arts and Design in Bratislava in 2015, where he studied Photography and New Media. Juraj took an internship at Fachhochschule Bielefeld in Germany in 2014 and has also participated at several international workshops in Slovakia, the Czech Republic and Germany. He has hosted 4 solo shows and been involved in more than 30 group exhibitions (including MARTa Herford Museum in Germany, MUSA’s European Month of Photography in Vienna, Institut Francais’ Month of Photography in Bratislava, Fotosommer Erfurt and more).

Untitled (Alert), from “The Curtain” by Juraj Starovecky

ERLEND LINKLATER

Erlend Linklater’s series “Borderline” follows the artist’s tracing of one of the world’s oldest extant borders: that between England and Scotland. Linklater, who followed the border with an Ordnance Survey map, says its “significance in shaping cultural identity, nationalist aspiration and bureaucratic wrangling was never more obvious than during the Independence Referendum of 2014 and continues following the UK’s vote to leave the European Union.”

Erlend Linklater (based in Kampala, Uganda) wonders what shapes us and why we are like we are—what is the tapestry of stories that moulds identity while influencing behaviour and belief. His photography seeks to explore these themes informed by his experience as a Scot living and working across Africa, South America and Europe for more than 20 years.

-2.33526, 55.63205, from “Borderline” by Erlend Linklater

DAQI FANG

Daqi Fang’s “Plastic Utopia II” is the second phase of a three-part series, in which the artist recreates landscapes first seen in dreams from satellite images drawn from Google Earth. These photographs speak to the disconnect between an absolute, quantified nature and the surreal plasticity of such data—which, as in Borges’s Library of Babel, can be rearranged in infinite possibilities, but only once it begins to resemble something of natural beauty does it take on significance. By including figures of himself, he also suggests the possibility of inhabiting this immaterial realm.

Daqi Fang (based in New York, NY) was born in China. As a visual artist, his work involves many forms, mainly photography, video, and visual installations. His interests lie in the fantasy of human’s existence and interactivity with nature. He had his work shown in Holocenter Gallery, New York, and has been widely featured in numerous magazines and publications in China.

Plastic Utopia II #2, from “Plastic Utopia II” by Daqi Fang

ABDULAZEZ DUKHAN

Abdulazez Dukhan will exhibit nine photos from his project “Through Refugee Eyes,” which documents his ongoing experience as a refugee of the Syrian civil war. His intention is to help amplify the voice of refugees, to draw the world’s attention to their desperate situation. “Your eyes are the way toward the truth, you can realize everything through them,” he states. “Through photography and through art I am trying to connect with your eyes. I am trying to tell you a thousand words, a thousand stories from the other world!” Having fled their war-torn homes, they now find themselves trapped between borders, in the bewildering no-man’s-land of the camps.

Abdulazez Dukhan is an 18 year old Syrian refugee from Homs who, since his arrival in Idomini, Greece, has been detained in numerous camps within the country. After being gifted a laptop and camera by a voluntary aid group, he has used his photography to provide a passionate voice and platform for displaced Syrians. His project “Through Refugees Eyes” has attracted international attention, and his work has been exhibited in countries as diverse as Spain, Italy, Jakarta, China, Canada, and the US.

Sleep Deeply, from “Through Refugee Eyes” by Abdulazez Dukhan

SPONSORS

New York Photography Diary would like to thank our generous sponsors, without whom this exhibition would not be possible.

An East London Fine Art Trade Guild-accredited photographic and fine art printer, and champion of emerging artists.

Elegantly simple professional picture hanging systems.

Perhaps because I am a writer myself, what I found to be the most communicative element of No Circus, however, was D.J. Waldie’s beautiful and poetic introductory essay, which snaps the images together thematically and then expands them into a thousand directions. Oscillating between tender personal narrative and an informative overview of fumigation and its many associated dangers, Waldie’s essay sets a dark and contemplative tone over the entire project, occasionally pulling on heartstrings and letting them resonate all the way back to childhood. After a discussion of sulfuryl floride and chloropicrin, the poison gases used to break down termite’s bodies, a short blank stretch of a paragraph break leads us to his own boyhood. He’s playing hide-and-go-seek with his brother, and finding himself standing alone in his bedroom. “Because I’m small, the room seems large. And I’m afraid. My knees actually begin to knock out of fear. I’m afraid of what isn’t in the room. I fear my own absence.”

Perhaps because I am a writer myself, what I found to be the most communicative element of No Circus, however, was D.J. Waldie’s beautiful and poetic introductory essay, which snaps the images together thematically and then expands them into a thousand directions. Oscillating between tender personal narrative and an informative overview of fumigation and its many associated dangers, Waldie’s essay sets a dark and contemplative tone over the entire project, occasionally pulling on heartstrings and letting them resonate all the way back to childhood. After a discussion of sulfuryl floride and chloropicrin, the poison gases used to break down termite’s bodies, a short blank stretch of a paragraph break leads us to his own boyhood. He’s playing hide-and-go-seek with his brother, and finding himself standing alone in his bedroom. “Because I’m small, the room seems large. And I’m afraid. My knees actually begin to knock out of fear. I’m afraid of what isn’t in the room. I fear my own absence.”

Coleen MacPherson

Coleen MacPherson To quote the famous dictum: writing about music is like dancing about architecture. With that said, I would gladly watch someone dance about architecture, if the opportunity ever came along. While I have yet to read Geoff Dyer’s book But Beautiful: A Book About Jazz (1991), in which he writes about music (or dances about architecture – I honestly haven’t read it), his writings about photography in The Ongoing Moment (2005) are often as innovate and freshly conceived as I imagine a foxtrot about Brutalism might be.

To quote the famous dictum: writing about music is like dancing about architecture. With that said, I would gladly watch someone dance about architecture, if the opportunity ever came along. While I have yet to read Geoff Dyer’s book But Beautiful: A Book About Jazz (1991), in which he writes about music (or dances about architecture – I honestly haven’t read it), his writings about photography in The Ongoing Moment (2005) are often as innovate and freshly conceived as I imagine a foxtrot about Brutalism might be.