Photo Romania Festival 2016

There is a buzz and a joviality in the air at the 6th edition of Photo Romania Festival. I arrive at Sapientia University half way through the five day programme, warmly welcomed by festival organiser Sebastian Vaida and ready for a day of talks and discussions. I watch as friends and colleagues fill the building, their welcoming embraces and friendly chatter reminiscent of a family reunion, and one by one I am introduced to this amiable bunch. For many this is a fixed event on their social calendar. The desire to support each other and extend the reach of photography is uniformly shared, with many attendees part of PHEN (The Photo European Network) and hailing from all over the EU. The infectious passion and comradery is one of the defining characteristics of the festival, helping bring everything together with a sense of purpose.

Despite a pleasingly casual vibe (we’re on “Romanian Time” I’m told – meaning everything starts 15 minutes later than advertised) the festival comprises a packed schedule of events that take place across the beautiful, laid-back city of Cluj-Napoca. Among a number of guests Colin Ford is in attendance to give a talk on Hungarian Photography, as well as Keith Moss who is here to deliver a street photography workshop. Numerous in-depth presentations are lined up, detailing a compelling array of artistic projects, and practical sessions have been organised covering specialist topics such as wedding, fashion, landscape, and concert photography.

Sebastian calmly shepherds his guests and speakers into the auditorium as a day of talks begins. The variety of work presented is aesthetically experimental and intellectually incisive, often approaching difficult subjects in considered, thoughtful ways. Particularly fascinating is Gema Polanco Asensi’s discussion of her work Como Dios Manda (“As is Proper”) and her photographic investigation into how women are controlled for the benefit of male hegemony, through what Michel Foucault termed bio-power (the subjugation of bodies by modern nation states through a range of diverse practices). While bio-power is evident in a number of contexts, Asensi’s focus is “upper middle-class Spanish women”, using her own family as a case study and combining archive photos with her own work.

Como Dios Manda (As is Proper) 2016 © Gema Asensi

While she iterates that this method of female subjugation is seen the world over, it is noteworthy that her mother and grandparents grew up in the shadow of Franco’s Spain, where women were expected to submit to the traditional values of motherhood and family or risk being ostracised by their communities. Subsequently, internalising the values of this ruling power they pass on these ideals of femininity and subservience to their female offspring, confirming the effectiveness of a ‘silent’ kind of government where woman’s role as nurturer is just “common sense”.

Her pictures have a critical, sociological objectivity; many of them are cropped or blurred to obscure individual faces, drawing attention to their behaviours instead. These are often subtle gestures such as holding, touching or petting, acts codified as care but implying a form of physical and psychological control. The archive photos of her mother and grandmother are juxtaposed with Asensi’s recent work in which she becomes part of this recycling of hegemonic values. Through the comparison of old and new we see the same gestures recur, with the often de-personalised bodies playing the same roles: wife, carer and mother. One particular image, a mother’s hand on a young woman’s head as she brushes her hair, hints at the veiled nature of control. The subject of the picture is subdued, groomed; being moulded perhaps into an object of attraction for a future suitor.

Johan Österholm’s series Peculiar Notions at Dusk conflated the cosmic and the ordinary with an Isaac Newton inspired investigation into the fall of that fateful apple. Covering the cross sections of fruit in a photo-sensitive emulsion he then exposes it to starlight to create “a cosmos within the apple”, resulting in some stunning images. Taking a more socio-political turn, Juraj Starovecký’s The Curtain explores our ongoing enforcement of arbitrary and unnatural barriers. Reanimating the “Iron Curtain” era for a generation born after the Cold War, he illustrates the extreme obstacles encountered by those either wanting to enter or leave Soviet-Russia between 1945 and 1991. In a more personal, nostalgic vein he also investigates childhood and memory; in Familiar Story cutting out the faces of his family photos to disrupt one of the central purposes of photography – to document and record our lives – while allowing other people to project themselves into similar situations from their past.

Mangrovines, 2016 © Jonas Forchini

I’m taken by the suggestive nature of Jonas Forchini’s Mangrovines (currently exhibiting at PhotoEspaña along with Asensi’s Como Dios Manda). Illuminating the difficult situation of many Senegalese, who in the past have made a living from artisanal fishing in their home country, he describes how their livelihood has been threatened by the over-exploitation of their waters by European fishing boats. The stark minimalism of a number of his images (ropes transcending black space or a blanket looped through a single rope as though through a noose) evokes the tenuous existence of these men. “The sea becomes asphalt” when they are forced to emigrate, here to the urban milieu of Madrid, where they make a living through the illegal activity of street-selling.

Forchini is sympathetic to their dilemma and interested in how they adapt to their new environment. He draws out the parallels between their old native trade and their new prohibited one. The fishing net which contained their catch before becomes the blanket with their cache of illegally sold goods. The rope conflates the fear of being caught by the police with that of the fishing line. As well as this, the symbolism of the stretched rope, continuing beyond the frame and often knotted, suggests to me the interconnected global web we are all a part of; our actions always having consequences, on communities or the environment, whether we are aware of them or not.

Breaking for lunch, we coalesce in the courtyard just outside the university, amiably chatting as we spoon plates of food into our mouths. Sitting with the very personable Henriette, a representative from Nordic Light Festival and a member of PHEN, we express an impatience to explore this beguiling city. As soon as we are told there are numerous exhibits in the Casino building in Central Park, not more than fifteen minutes away, Henriette’s blue eyes disappear behind dark shades and we are off into the sunny streets, heading towards the warm heart of the city.

The park is awash with activity. Medieval street theatre greats us, though my Romanian doesn’t stretch much further than “Excuse me” and “Can you speak English?”, so to me it is just men with plastic shields mouthing off on horseback. There is also a stunning lake in the park on which kids peddle huge car-shaped boats (best idea ever!). We are stoic though and, refusing to be distracted for long, enter the Casino building.

Casino building, Central Park

The majority of the spare, rather empty hall is given over to the works of the renowned Romanian photographer and journalist Iosif Berman, whose black and white pictures adorn the orange walls. Living from 1892 to 1941, he was a socially committed photographer fascinated by rural Romanian life and its customs. His expressive images attest to this. He shows the material lack of these areas, as well as the simple joys of the inhabitants and their warm and generous spirit. On icy landscapes men are pictured labouring, axes caught mid-swing. Children sit covered head to toe in the snow, their mouths open in joyful cries, while in a cemetery a large group kneels by the graveside as though performing a ritual. Given the absence of captions, one infers that this work was produced as part of his partnership with the sociologist Dimitrie Gusti, part of their contribution to the then emerging genre of ethnological photography.

In the same building Cătălin Munteanu’s After 25 Years: The Closed Gates of the Industry in Ploiești (2014) explores the steady decline of the aforementioned city, just north of Bucharest. Once a place of great civic pride for its industrial might – it was home to the world’s first oil refinery – the fall of communism in 1989 arguably led to its collapse, resulting in the loss of hundreds of thousands of jobs, along with the closing of vocational facilities that provided training for employees. As capitalism took over, a once self-sustaining economy began to rely on imported goods, and its landscape became littered with abandoned buildings and shopping malls.

The images displayed present a lost world through the bleached bodies of disused factory buildings. A power station sits idle behind rusting green gates and crumbling walls. Only a station attendant stands in front of Ploiești West’s neglected and peeling facade. Nature is seen reasserting her supremacy where time has been called on human endeavour, creeping over walls and burying railway track. Apart from a few resigned individuals, the photos are desolate and uninhabited, full only of broken glass and corroded metal. “This”, Munteanu says, “is the progress of 25 years of wrongly understanding capitalism and democracy.”

After 25 Years, 2014 © Cătălin Munteanu

On the way back to the university I indulge in a delicious sweet-cheese pastry from a local bakery, and when I return, tanned and full of sugar, I’m somewhat sleepier than before. A talk on the use of fairy-tale elements in fashion photography presents some imaginatively designed shots, and surreal scenes of fair-maidens parade before my drooping eyelids. I can’t be sure I’m not dozing when the phrase “You used the unicorn…I didn’t do that” reaches my ears. As evening slowly descends and the day’s events draw to a close I head back out into the warm air, passing by Avram Iancu Square with its cathedral and towering statue before leisurely walking to Samsara, where the Photo Romania crew in celebratory mood eat and drink late into the evening.

The next day I head for Casa Romania: the headquarters of the festival’s operations and informal chill out zone. Ascending the hill in the 24 degree heat I pass some fantastically dilapidated houses, held back behind tall iron gates like something from a horror movie (we are in Transylvania after all!), before finally spotting the exultant words “PHOTO ROMANIA” along a fence. Here a large number of the photographers’ works are displayed, as well as being the place where PHEN are holding their day-long discussion. Irina, providing support and coordination for the festivals day-to-day activities, sits cheerful and diligent behind a laptop at a table strewn with flyers, and I potter about taking in the weird and wonderful décor and a lot of fine photography.

Arresting monochrome pictures from Javier Corso’s Fish Shot are stretched out across two rooms, part of a documentary project investigating the interwoven issues of loneliness, isolation and alcoholism in Finnish society. There is a stark beauty in the sprawling shots of barren landscapes, the emptiness evoking a sense of unease. Geographical isolation is shown to be part of the problem, while social atomisation is evident in the fact the majority of these photos show men journeying alone. This is potentially the flip-side of Finland’s successful welfare state and its plentiful housing, reducing the necessity for co-habitation and additional networks of support.

Fishshot, 2015 © Javier Corso

The spectre of oppressive emotion is implicit in a number of images, and the motif of the axe recurs, symbolic in Finnish culture for “the violence”. In one shot it is expressionistically lit, like a still from The Shining. In another a man sits in a sauna, one hand with a beer and the other to his downcast face, the feint reflection of a woman behind him, suggesting a narrative of gender-based violence and male shame (heavy drinking is present in more than 50% of suicides and homicides in Finland). Powerfully expressing the cyclical nature of the problem is a photo of a man submerged in water, only his hand visible as it breaks the surface; showing both the suffocating emotion and subsequent immersion in alcohol to cope with it. “The pictures try to evoke a daily situation for many people in Finland”, Corso explains. “The social pressure to drink, trying to forget the loneliness.”

Well-known for his iconic images of festival revellers and swaggering rock bands such as AC/DC and Guns ‘N Roses, Miluță Flueraș presented a slightly more subdued collection of images with Taking my Time to Pay an Homage. A tribute to “the living moments before the disaster” that occurred at Colectiv nightclub in Bucharest on October 30th 2015, the series memorialises those killed in the deadly blaze. A big supporter of the band Goodbye to Gravity, Flueraș was there to cover their free concert when the venues’ polyurethane ceiling caught fire, a result of the bands pyrotechnics. 64 people were killed, including band members Mihai Alexandru, Bogdan Enache, Vlad Țelea and Alex Pascu.

Taking My Time To Pay An Homage, 2015 © Miluță Flueraș

Given the knowledge we have of the subsequent events, it is difficult not to read these pictures in a foreboding and melancholy way (especially one of the lead singer flanked by lit sparklers and a flame-illustrated band banner). Flueraș’s intention though is not to present a sombre view of what occurred but the opposite: to commemorate “a great band [who were] very underrated” and to convey the joy and excitement at the venue, with shots of the crowd “bursting with happiness.”

He has a keen eye for drawing out the empathic connection between an audience and performing artists. A monochrome shot of the crowd taken from across the stage captures the band’s guitarist looking out into the sea of people, mostly obscured in shadow except one boy’s face, metaphorically and literally lit up, smiling beatifically. Other shots, streaming with bright lights and colour, show the bands immersion in the music as they jump up and down, storming the stage with eyes full of passion. Watching them perform their rousing song “The Day we Die” on YouTube, I’m reminded that rock music is all about defiance and rebellion, and a rallying cry against the most pedantic jobsworth of them all, death.

Taking a break, a few of us sit in the sun eating lunch and sipping coffee, including the laid-back and engaging Simone from Newcastle Photography Festival, something of Photo Romania groupie and Cluj fanatic. A few people bid adieu, Gema and Jonas among them as they return to Spain for the next instalment of their photographic saga at PhotoEspaña. I return indoors, intending to peruse halls lined with the work of native Romanian photographers, but it is hard to be industrious when everyone is so outgoing. This is just one of the things that makes the festival such a joy: a genuine sociability that extends beyond mere networking.

I head off downtown, determined to visit at least one more exhibition before my time here comes to an end. It requires all my navigational and Romanian language skills to locate the café where the group show Layers is being held. Naturally, lacking said skills, I yo-yo up and down Strada Universităţii numerous times. I am also distracted by the huge crowd that has amassed in Unirii Square, and briefly join them in being captivated by an operatic onstage performance. Finally, and with lots of help, I find the elusive Insomnia Café. All that is now required for me to do is convince the manager that she does indeed have an exhibition there to show me.

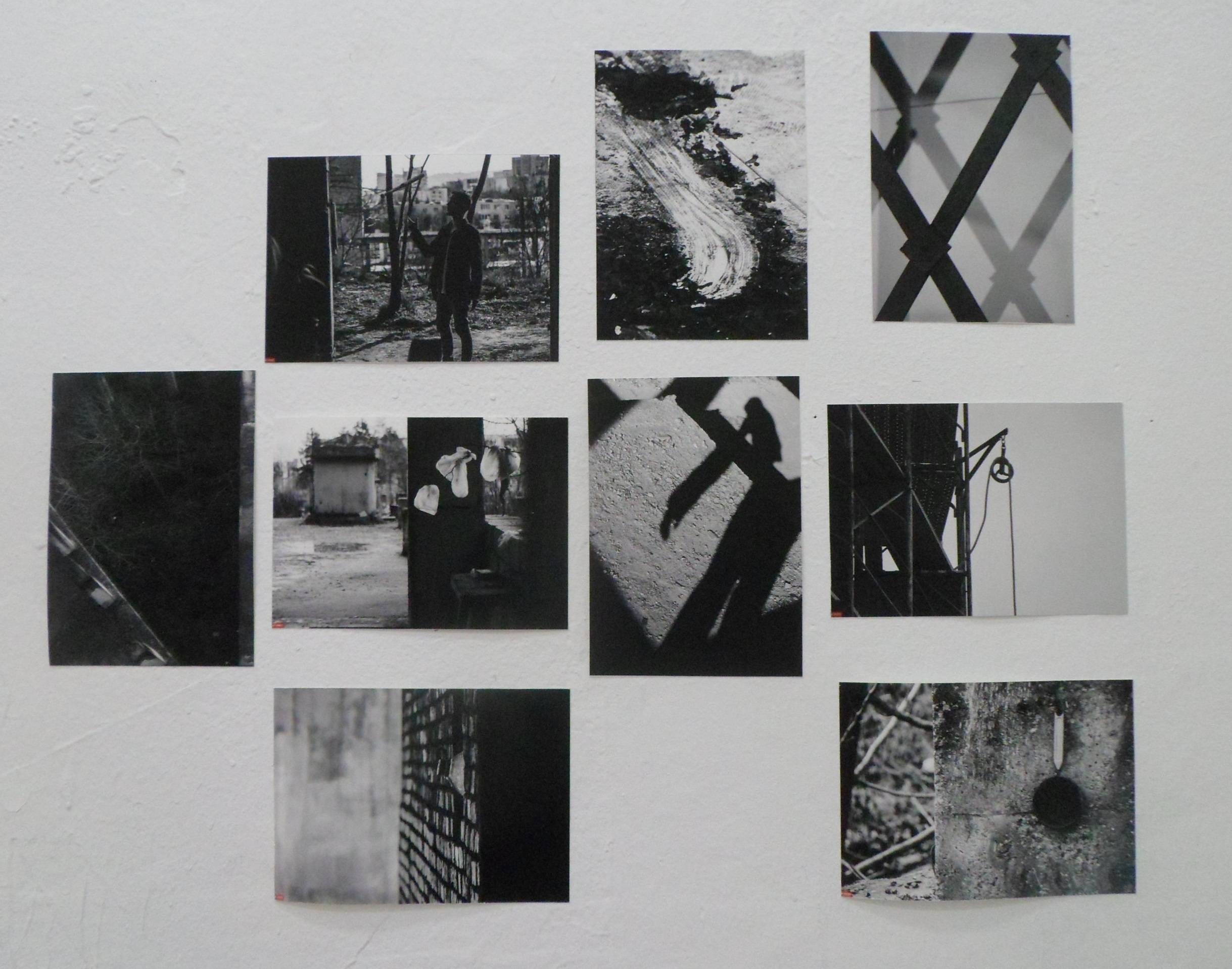

Eventually I’m taken to a very sparse, functional room (i.e. it has walls). But though the space is underwhelming, the photography is thoughtful and eye-catching. Most of the images are not much bigger than postcards, the majority shot in black and white and presenting what I assume to be the anonymous, underdeveloped side of Cluj. From my brief time here, the city certainly seems to have a dilapidated charm equivalent to Berlin; impressive architectural and grand historic monuments vying with a plethora of stoic but cracked facades.

Layers show, group exhibition

As the show’s slightly cryptic mission statement attests, it is an exercise in “beautifying a city in which oldness, poverty and poor environmental taste is pretentiously displayed, like inadequate makeup.” The images are visually compelling and abstract, the majority aestheticizing architectural ugliness, shifting our perspective away from the social to the purely visual (the shots also suggests a clandestine gaze occupying these neglected urban ruins). The empty shells of buildings are shot with a pleasing symmetry and depth; stairwells crisscross and shadows contribute their own geometry, creating multi-layered images. Unusual vantage points are presented, with photographs opening up into Escher-like dimensions. We are encouraged to see differently by focusing on the combination of shapes, patterns and complimentary angles, rather than the neglected and decaying structures that form the ostensible subject of the frame.

It is with a touch of reluctance and a smile on my face that I leave Photo Romania Festival and the easy-going vibes of Cluj-Napoca. The people and my experiences there have been a real pleasure, and while also promoting Romanian photography the festival showed itself to be a truly cooperative, international affair. Before I head back to the UK though the remainder of us dine together at Casa Tiff. Radu, aware that I am a stranger to the enticements of Palincă (a highly alcoholic Hungarian fruit brandy), kindly places a shot of the spirit in front of me. I knock it back without question and it’s like a small atomic bomb going off in my oesophagus. I’m somewhat disconcerted by the anxious faces looking back at me, but against expectations I stand up and walk in a straight line out of the restaurant, retaining consciousness all the way back to the hotel.

– Daniel Pateman

Special thanks to Sebastian Vaida for his hospitality and for making my attendance possible.

Daniel studied Humanities and Media at Birkbeck University and continues to indulge his abiding interest in the arts. He has enjoyed writing since a young age and currently produces articles for a number of online publications. He keeps a blog called The End of Fiction, consisting of his poetry, prose and other creative work, and is currently looking to forge a new career in the creative industries.

Daniel studied Humanities and Media at Birkbeck University and continues to indulge his abiding interest in the arts. He has enjoyed writing since a young age and currently produces articles for a number of online publications. He keeps a blog called The End of Fiction, consisting of his poetry, prose and other creative work, and is currently looking to forge a new career in the creative industries.

Céline Bodin is a French photographer. She graduated from a photography BA at Gobelins, L’école de l’image in Paris, and in 2013 she moved to London to complete a Photography MA at the London College of Communication. As well as regularly writing about photography, Céline works closely with London universities and galleries. Her photography practice revolves around the themes of identity and gender in the frame of Western culture, as well as landscape photography and the philosophy of the Sublime.

Céline Bodin is a French photographer. She graduated from a photography BA at Gobelins, L’école de l’image in Paris, and in 2013 she moved to London to complete a Photography MA at the London College of Communication. As well as regularly writing about photography, Céline works closely with London universities and galleries. Her photography practice revolves around the themes of identity and gender in the frame of Western culture, as well as landscape photography and the philosophy of the Sublime.

The first of my photographic forays is Alec Soth’s Gathered Leaves at the Science Museum.

The first of my photographic forays is Alec Soth’s Gathered Leaves at the Science Museum.