Great sculptures are engaging from any perspective. Whether viewed from the back, side or front, they offer their audience something to consider. Similarly, great exhibitions hold up under the myriad angles from which they might be approached. An awareness of one’s own personal perspective is important to bear in mind when viewing the Brooklyn Art Museum’s current photography show exploring Israel and the West Bank, This Place, on view through June 5th, 2016. Organized by Frédéric Brenner (his work is also featured) and curated by Charlotte Cotton, the exhibition features 600 works by twelve artists, who are not Palestinian or Israeli, but who came to Israel and the West Bank between 2009 and 2012 to create work for this project. Likely this conceptual decision was made with the intention of making the exhibition as unbiased as possible—and to work around the cultural boycott which inhibits Palestinians and Israelis from working together; however, this choice also limits the windows we are given into “this place.”

I, for one, came to the show with the personal experience of having spent three weeks in the West Bank in 2013 teaching photography to Palestinian youth, and I came away from the exhibition feeling like their story—and the story of the larger Palestinian population in general—was not properly shared in the exhibition. There are only hints of the daily drudgery and harassment experienced by Palestinians. Missing from the overall exhibition is any discussion of the issues surrounding ID checks for Palestinians and the limitations on their movement throughout the West Bank, East Jerusalem and Gaza. Gaza itself was completely missing. Most problematic, several large scale portraits of Israeli settlers by Nick Waplington and Frédéric Brenner, which show whole Jewish families at dinner or assembled in front of or inside their homes, are not matched in any way by similar representations of Palestinians. This absence gives the message that only one group has ownership of this place.

As outsiders, the photographers in this exhibition had to decide whether or not to engage in political commentary or develop relationships with the communities they worked within. For the most part, it seems, the artists avoided taking positions. While Gilles Peress’ street photography, for instance, focused on Silwan, a village just outside the walls of old Jerusalem, the ongoing demolition of Palestinian homes there was not in any way present in his images. This comes across as a considerable misprision when one considers the unblinking eye with which Peress has looked upon such conflict zones as Bosnia, Rwanda and Northern Ireland.

Instead of the struggles between Palestine and Israel, the land itself is an important theme in this exhibition. The first major room features several bodies of work that illustrate landscapes, empty of humans. While this works to focus our attention on the environment, it also reinforces the impression that this is an an unoccupied, promised land, waiting for colonization. I kept looking for the scenes I had witnessed first hand of old Palestinian men tending to olive trees, farmers standing in wheat fields, children shepherding or harvesting potatoes. They are not present.

The empty landscapes and cityscapes of Stephen Shore’s work reminded me of the trope “a land without people, a people without a land,” used to justify the Zionist colonization of Palestine after World War II. Meanwhile, the drone-perspective of the Sinai Desert captured in Fazal Sheikh’s aerial photographs is texturally and conceptually interesting, as is the visual range given between the high elevation landscape photography and his portraiture (the latter are not present in this exhibition but can be found in the museum’s gift shop in Sheikh’s photo book set). Sheikh’s title for this series, Desert Bloom, is an ironic commentary on Israel’s first Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion’s historic promise to “make the desert bloom” through Jewish settlement.

Daybreak, a large scale photograph by Jeff Wall greets you at the entrance. It depicts a small group of Bedouins sleeping in an open field on tarps under cheap Chinese-made blankets, an Israeli prison rising in the background. Wall recreated the scene after witnessing it on a previous visit. While this is the artist’s standard working process, here it also simulates a core concept in the creation of Israel: the act of recreating a remembered reality. And while provocative and poignant, this shot also reinforces the image of the Palestinian as a vagrant and temporary nomad of this land.

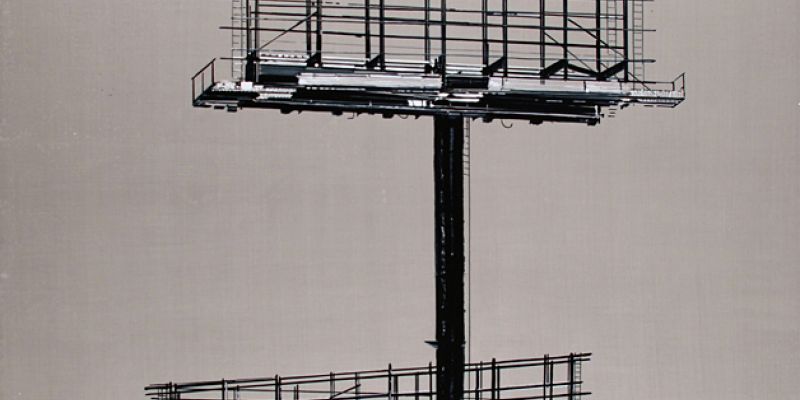

Although many of the works that Rosalind Fox Solomon produced for this project address the “othering” that is done so well in this region, they are not included in the exhibition. They can be seen in her book, judiciously titled THEM. The works presented in the exhibition extend her interest in the odd among us but come across more universal in theme and less specific to the subject of Israel and Palestine. In some ways the most disengaged was Jung Jin Lee, whose large scale black and white photographs of stark landscapes and man-made objects could have been from any place in the world. Yet, the photo of the tightly bound bale of barbwire, sitting alone in a barren landscape do speak volumes about the forces of war and national borders.

Wendy Ewald, despite her initial disinterest in working in Israel, takes many brave forays into both the Israeli and Palestinian worlds. The American photographer and educator chooses not to present her own photographs, instead she teaches photography skills within communities and then collects and curates the photographs they produce. In this series, she collaborated with diverse student populations (Muslim, Druze, and Christian) of The Sisters of Nazareth, the Melach Haretz Military School, and the Stateless Al Nawar (or Gypies), to name a few. The images are printed postcard size and presented in groups within a wooden large frame. The display format for this work is beautiful, if somewhat overwhelming—the impact lessened somewhat by the sheer number of images–but Ewalds appears to stand alone in bringing together the opposing sides of a conflict through her work and opening a window to their voices and lives.

Recognizing the strength of my own perspective, I made a point of asking a wide range of visitors for their impressions. Two dual citizens of Israel and the United States, a husband and wife, gave me valuable insights: the husband pointed out the although the Israeli settler portraits by Waplington and Brenner are powerful in their large scale presence, they represented the fringe of Israeli life. “They are not the average Israeli. We had not ever even seen the sect which wears the covering over their eyes. They exoticize us in these portraits.” The wife felt the photography was balanced but had real problems with the artists’ statements, feeling they all slanted “to the left – just like all exhibitions on Israel in New York City.” Frédéric Brenner’s statement, for example: “Repairing the world begins by repairing the world in us. There is no other promised land. It belongs to no one and to everyone. It is everywhere awaiting our return.”

In almost every instance of the feedback I received, Josef Koudelka’s installation elicited the strongest praise or criticism. Installed in a waist high viewing case, a concertina book with images of the separation wall traverses the first large room of the exhibition—acting as a wall itself. For many, this book brought out the strongest emotions and responses. The stark black and white photographs, the relevance of this wall to our own border issues, and a text that clearly explains the Palestinian community’s struggles with its existence, contributed to this reaction. The Israeli couple felt that Koudelka’s presentation of the subject did not share the Israeli perspective over the wall.

While This Place gives us many views of Israel and the West Bank, it reinforces some concepts about the region that need to be looked at more frankly and bravely. Though, regardless of one’s perspective—in this case, my own—this is still an important show worth your time and consideration, from all angles.

On view now through June 5, 2016

Todd Drake is a photographer, educator, and human rights activist. His exhibitions tours nationally and he has worked most recently overseas in Palestine and the Turkish-Syrian border. A teaching artist for BRIC Arts Media, Drake lives in Brooklyn, NY.

Céline Bodin is a French photographer. She graduated from a photography BA at Gobelins, L’école de l’image in Paris, and in 2013 she moved to London to complete a Photography MA at the London College of Communication. As well as regularly writing about photography, Céline works closely with London universities and galleries. Her photography practice revolves around the themes of identity and gender in the frame of Western culture, as well as landscape photography and the philosophy of the Sublime.

Céline Bodin is a French photographer. She graduated from a photography BA at Gobelins, L’école de l’image in Paris, and in 2013 she moved to London to complete a Photography MA at the London College of Communication. As well as regularly writing about photography, Céline works closely with London universities and galleries. Her photography practice revolves around the themes of identity and gender in the frame of Western culture, as well as landscape photography and the philosophy of the Sublime.

The first of my photographic forays is Alec Soth’s Gathered Leaves at the Science Museum.

The first of my photographic forays is Alec Soth’s Gathered Leaves at the Science Museum.