Landscapes derived from representations of landscapes, Orogenesis (2002 – 2006), is a series of digitally constructed landscapes created using software designed for scientific and military purposes by Spanish visual artist and academic Joan Fontcuberta. Fontcuberta uses software called Terragen to create photorealistic visualisations of landscapes, but instead of using cartographic data as this software is designed to use, Fontcuberta has replaced it with canonical images of landscapes taken from the history of art. The title, meaning mountain building or formation, derives from a field of physical geography and an early indication of a multidisciplinary practice that borrows from diverse critical disciplines. The series is the manifestation of a complex layering of ideas and concepts, and has at its core, his key creative concerns of: ‘representation, the nature of signs and the relationship of pictures to the real world’. It may even seem tenuous to discuss Joan Fontcuberta’s practice as photographic, as this is a set of images are created using visualisation software – but it is absolutely key to understanding Orogenesis, which is as much about photographic representation as it is the historical construction of assumptions about the subject.

Discourse around the time of the introduction of digital photography in the late 1990s was fearful of the death of the photographic medium; a mirroring of reactions to other changes in photographic culture historically, such as the introduction of colour film. Colour photography was only initially accepted as a commercial or a vernacular type of photography and the digital medium has followed that same path to acceptance. Joan Fontcuberta began his career in advertising, which may explain his willingness to utilise new representational tools. Contemporary assessments are less fearful of ontological change as Sarah Kember points out ‘how can we panic about the loss of the real when we know (tacitly or otherwise) that the real is already lost in the act of representation? Any representation, even a photographic one, only constructs an image idea of the real’.

This represents a sensible shift away from the anxiety of a ‘post-photographic’ discourse that digital photography represents an entirely new medium, and acceptance that any image is never completely truthful. With Orogenesis, Joan Fontcuberta is taking this one step further and posing a challenge to what is now accepted about digital image representation by using visualisation software. The process, though, is still inherently the same in a tradition sense. Like a digital photograph, created with a digital camera, a Terragen image is constructed using data. Rather than it being created through the digitisation of light waves, an image is created through the algorithmic processing of cartographic data; creating impressive photorealistic results through a mimetic process. Fontcuberta has replaced light with code, and the real life subject, made visible through light, is replaced by an artist’s representation of a subject from real life. This forms the basis of Fontcuberta’s strategy and is successful at stimulating discourse on the subject of representation in the digital and information age, while also reflecting on histories of photographic representation.

Through this method, Fontcuberta also reflects on the relationship between the photograph and its original, especially with the use of the art object as the basis of representation. When Orogenesis is presented, whether as a photograph or a book – and both are primary ways of viewing the work, it is always in reference to the image suppling the initial data. This original referent landscape, borrowed from the long history of art and photography – for example Orogenesis Stieglitz (2005), is always shown alongside a small version of the original work. This inclusion could be compared to a thumbnail, a function of computing that assists navigation, and reveals not only how recognisable these canonical source images really are, but creates an accessible route into the meaning of the artwork. The titles of each individual piece, with the inclusion of the creator of the source landscape image, also implies a form of collaboration or collusion with the original and an acceptance of the role of copying and appropriation as a viable visual practice, in agreement with Rosalind Krauss’s critique of modernist ideas of originality; that works of art are never unique as an artist is always influenced by external forces. Therefore, Orogenesis evokes age-old practices of copying from the history of art, as Joan Fontcuberta himself states: ‘just as every image derives from some other image that preceded it, so all histories, too, derive from other histories’.

The work becomes one of repetition with antagonism. Patricia Keller describes the process as ‘perpetuated and disrupted’, between the past and the present. Much like Sherrie Levine’s After Walker Evans: 2 (1981), where Levine appropriates Walker Evan’s photograph, by including it in the presentation of the work at only a fraction of the size. But rather than re-photographing like Levine, Fontcuberta is re-processing the original and the before and after appear to be different. The original landscape remains indexical to the final computer generated landscape. Even though the result has removed recognisable signs of the original, the traces of its existence remain. That Fontcuberta is using the art object is also significant in this respect, implying a criticism of the value of the art object that also raises concerns associated with authorship and ownership. Fontcuberta relinquishes control of the creative process – the result is placed in the hands of Terragen, and ensures that the authorship of Orogenesis is multiplicitous and ambiguous.

As a representation of art historical ideas, the work is obviously critical of modernist art historical discourse and embodies a postmodern approach. As Geoffrey Batchen states in his essay that accompanies the book Landscapes Without Memory (2005): ‘in Fontcuberta’s hands, photography has become a philosophical activity, not a pictorial one’ which is only emphasised by Fontcuberta’s extensive critical and theoretical writings. While this comment could be seen as a vague generalisation that encompasses the majority of postmodern, even post-war, art practice and potentially undermines visually interrogative techniques, it is correct in the sense that Fontcuberta is heavily relying on textual philosophical ideas through the Orogenesis series. Fontcuberta does accept that aesthetics are not primary within his investigations, ‘a by-product’, yet an essential way of communicating and encouraging critically engagement from the viewer.. This once again stems from Fontcuberta’s experience of advertising and visual rhetoric.

It is clear to see how Fontcuberta is combining ideas associated with language, semiotics and signs, with photographic representation. But any philosophical activity of this particular kind would not exist without the pictorial. Joan Fontcuberta’s critical writings are permeated with the word ‘crisis’ and whether this is a crisis of history, art or our landscape, it reveals a desire to question historically pre-conceived notions within our culture. As he discusses in a ‘virtual roundtable’ as part of Ecotopia, an exhibition of landscape photography and video associated with environmental issues: Postmodernism, the society of the spectacle, the capitalism of fiction, and the age of melancholy have combined to consolidate a philosophy of suspicion, a mistrust of a reality composed of simulations, manifested in an avalanche of seductive, saccharine images – to which it is imperative to be critical. Fontcuberta highlights how the philosophical environment of our time encourages the need to interrogate our general engagement with image representations but with the need to remain constantly critical. This statement also provides some indication why Batchen would associate the virtual landscapes with stock photography with its kitsch, generic-looking imagery. Stock photography represents a blandness of mass-produced images produced for commercial gain bound up in issues of copyright and ownership and resonates with an artist critical of a world homogenised by globalisation and the commodification of the art object.

Both series represent the power of the internet to disseminate information and imagery, as a new platform for the social, as well as artistic practice and criticism. Fontcuberta is also asking the viewer to question whether that information is authentic. Batchen states that the digital distribution of information is ‘the social/political issue of our age’ and becomes even more poignant when Fontcuberta is simultaneously challenging what is considered traditional and safe: landscape. It is now accepted that, as an art historical and critical subject matter, the representation of landscape is not objective but a complex mix of cultural, social and political constructs. This is what Joan M. Schwartz and James R. Ryan in Picturing Place: Photography and the Geographical Imagination (2003) would describe as the ‘geographical imagination’ and a learned, culturally constructed way of seeing, stating that: ‘The taking and viewing of photographs was an integral, active and influential part of engagement with material reality, helping to construct imaginative geographies’. Joan Fontcuberta uses Orogenesis as a vehicle to both highlight and contradict how place exists through time and memory.

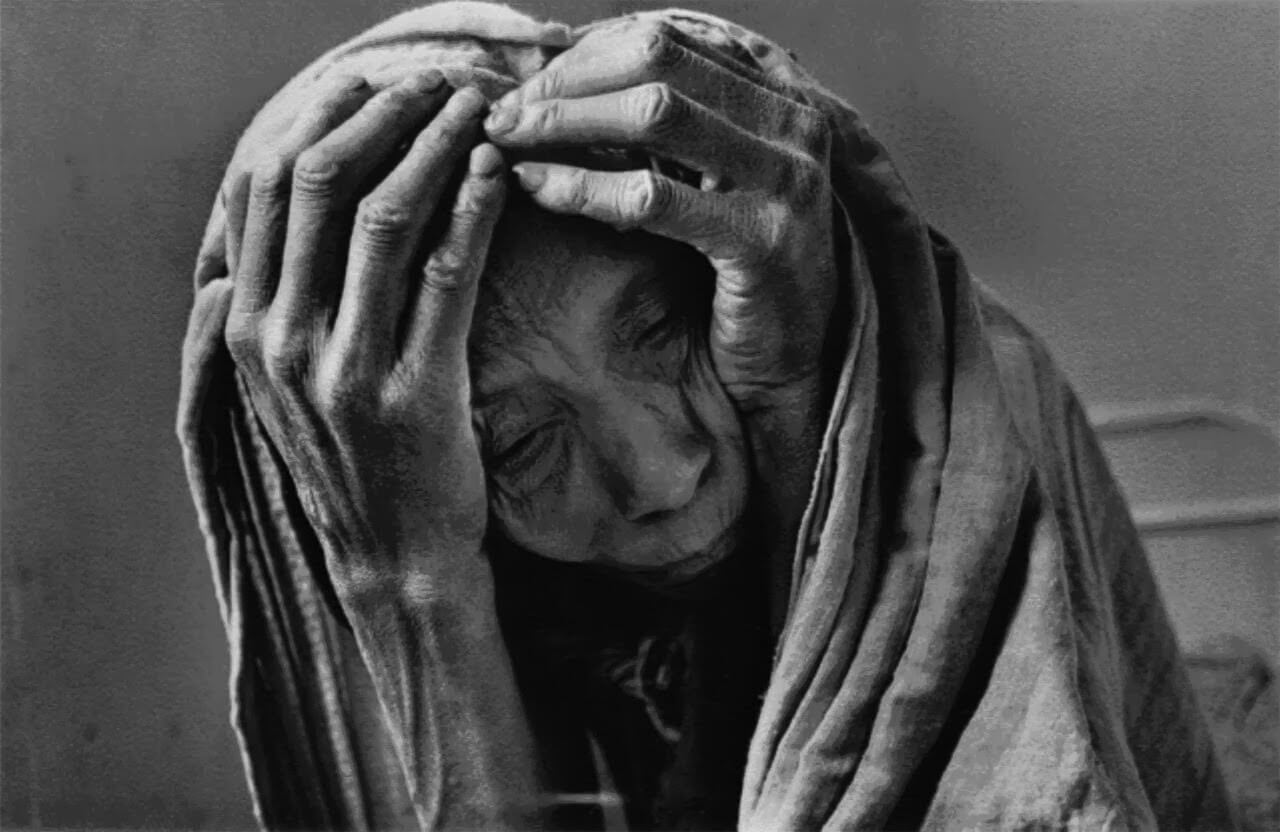

The artist uses embedded connotations of power relations (gender, race, class, colonialism) that have preoccuppied photographic discourse by disrupting and attempting to remove them from his landscapes, which highlights just how embedded our historically constructed ways of seeing really are. Orogenesis, or Landscapes Without Memory as it would now be appropriate to use, becomes a series of landscapes without history, without memory and without place. Fontcuberta’s title may reference Landscape and Memory (1995), Simon Schama’s seminal book about the environment and collective memory, as another nod to the critical climate that he is deconstructing. As the original data also comes from the history of art, notions of the ideal landscape, the pastoral idyll or the romantic sublime, are further emphasised, especially as Terragen interferes with that information. By turning an idealised representation of a landscape into another idealised representation, Fontcuberta is bemoaning the loss of our natural environment – another social and political issue of our time. Fontcuberta states that the work ‘can also be understood as samples of those fantasy “other worlds” where we will find shelter when our environment no longer supports life conditions.’

Orogenesis becomes a utopian vision full of contradiction and anxiety as it teeters on the cusp of the real and unreal, familiar and alien. The antagonism of these dualities deconstructs historical and cultural ideals before the eyes of the viewer with great unease. This disquiet goes further when considering the role surveillance and the historical relationship between the photographic and reconnaissance. Consider Carleton E. Watkins heroic and canonical images of the American West, his commissioned photographs could be considered early forms of reconnaissance, a mapping of a new landscape to enable to the spread of capitalism. Also considering the development of reconnaissance photography during the First World War, a specialist skill in the reading of photographs like maps, and a tool of modern warfare. The relevance of reconnaissance to the Orogenesis project is highly significant. Terragen was developed for military and scientific purposes, in order to visualise large areas of potential battlefields with only cartographic data and the high view-point of all of the Orogenesis landscapes only emphasises the surveying nature of the images. Orogenesis was published at the commencement of the post 9/11 era of increasingly virtual and detached methods of modern warfare and the proliferation of drones, and criticality of this as much as of representation can be read through Fontcuberta’s process. Fontcuberta takes on board the anxiety of the information age and contemporary readings of Orogenesis must be influenced by issues relating to internet privacy and political and ideological approaches to data.

Bringing these principles of surveying and reconnaissance together under a single blanket heading of mapping, or cartography, Fontcuberta’s virtual landscapes are as much a critical engagement with this discipline as with photography or art history. Landscape photography and mapping are entwined areas of critical thought and cartography comes under the same critical scrutiny as photography with regards to the authenticity of representation. There are significant parallels between not only the properties of maps and photographs but also the history of cartography and that of photography. Mapping, as Denis Cosgrove eloquently describes it, is an act of ‘visualising, conceptualising, recording, representing and creating spaces graphically’ that can be ‘material or immaterial, actual or desired, whole or part, in various ways experienced, remembered or projected’. Cosgrove’s words could just as easily be used to describe photography and when considering Fontcuberta’s own introductory words, that this is ‘art as map’, the disciplines are further entwined. Also consider that both are tangible everyday objects and this can arguably also mean virtual and a further narrative layer of the art object is once again emphasised. Both a photograph and map are instantly recognisable, though it is necessary to decipher the surface in order to grasp its meaning and both involve the creation of some form of boundary or essentially imaginary frame. One must also see maps as agents of political and economic power and social mobility, much like landscapes and their photographic, or creative, representations and are subjected to the same amount of editing, selections, omissions and other subjective processes that are also inherently photographic and create meaning. Interestingly, the terminology used by Christian Jacob is the same as that used by Clement Greenberg when discussing the reality of a photographic image; that maps can be transparent and opaque, and shows how similar the critical discourse is. As Denis Cosgrove stated in the book Mapping (1999), postmodern theory also enveloped cartographic discourse: ‘a widely acknowledged ‘spatial turn’ across arts and sciences corresponds to post-structuralist agnosticism about both naturalistic and universal explanations regarding their single voiced narratives, and to the concomitant recognition that position and context are centrally and inescapably implicated in all constructions of knowledge.’

Denis Cosgrove’s insight is especially relevant to Joan Fontcuberta’s practice and his desire to challenge power, authority and what we know about information sharing. Much like the land and environment artists of the 1960s and 1970s, Fontcuberta disrupts time by applying mapping principles to exacerbate debate about memory and space. One can compare works such as Richard Long’s 1967 piece A Line made by Walking, London (Tate Gallery) to Orogenesis to show how mapping principles, combined with landscape as subject, can assist in deconstruction of time as associated with experience, while also criticising that beacon of realism: the documentary photograph. As Lucy Lippard writes in The Lure of the Local (1997): ‘for most of us the map is a tantalizing symbol of time and space. Even when at their most abstract, maps (especially topographical maps) are catalysts, as much titillating foretastes of future physical experience as they are records of others’ (or our own) past experiences.’ Yet while Long represents notions of experience by documenting performative gestures, Fontcuberta’s visualisations represent a complete obliteration of time and an eradication of experience, through the removal of history, narrative and memory. Any sense of place becomes unfamiliar and dislocated from its reference in time. Patricia Keller suggests that this results in forgetting, the ‘work of art as real map of an non-existent place’ entices the viewer to ‘rethink the paradox inherent in seeing these works as both real and fictional, as both the memory of the artwork and the remapped forgetting of that artwork’.

Time, in Fontcuberta’s work, becomes pivotal to its construction, representation and interpretation and the dissolution of time actively contradicts his consistently historical approach. Time also represents a decisive factor within the history of photographic technological development and has always had an effect on the type of work that is produced. The slow movement of heavy cumbersome plate cameras and long exposures infuse 19th Century exploration images. The desire to travel long distances to document a landscape is also apparent in the work of The New Topographics even though they had access to smaller snapshot cameras. Fontcuberta’s disintegration of time is magnified by the relative ease and speed of the creation of his digital landscapes,. As analogue photography started as an expensive time-consuming pursuit, so did digital photography, and it’s now cheaper and more accessible than ever – even Terragen can be accessed for free. It should be considered that Fontcuberta’s use of mapping creates, or perhaps reverts to, a mythical landscape. The creation of maps to represent social and religious importance rather than of actual place echos the earliest created maps of our surroundings. The viewer should also consider then the impact of the Enlightenment on the capturing of objective factual depictions as much with mapping as with the development and rise of photography that followed.

In Ecotopia, Gregory Volk describes how Fontcuberta’s ‘mythical’ landscapes initially ‘look plausible and enticing’ but because they ‘refer to no place on earth’ they ‘seem vaguely creepy and un-nerving’. This revulsion and anxiety that the viewer feels when attempting to decipher a place-less space teetering between the real and imaginary is that of the uncanny. Matthew Hart comes to a similar conclusion when writing about the work of Layla Curtis that: ‘the cartographic uncanny is the feeling one gets before a map that looks familiar and yet is also a chart of something very different; when the well known map of the well known territory no longer offers a reliable route through new thickets of fact and affect. The cartographic uncanny, then, marks both a failure of mapping and the persistence of cartographic reason under the sign of the failure.’ The failure that Hart describes parallels Fontcuberta’s own language, the ever present ‘crisis’, and resonates with Fontcuberta’s deconstruction of, not only, ideas associated with mapping but its contemporary criticism. The uncanny is an effective way of describing the response to Fontcuberta’s practice of representing critical contradictions that also mirrors the concept of the ‘uncanny valley’, a term coined Masahiro Mori in 1970 to describe a revulsion to images or things that almost look human, or real.

Orogenesis is a work full of antagonism, but perhaps also using humour and chance in response to notions of anxiety and control. Fontcuberta’s process is to trick the software into thinking that photographic representation of landscapes are maps. He is introducing the idea that the surface of an image could be codified in the same way as a map and disrupts an established process at the same time. He claims that this act of trickery represents his mistrust of authority gained from growing up under Franco’s authoritarian regime in Spain. This disruption means that the act of visualisation becomes an unknown, as the artist has cheated the system with little concern for how Terragen will respond except to produce a landscape. This is what Fontcuberta terms the ‘limited vocabulary’ of his chosen medium and it is in this regard that the work has much in common with that of the experimental composer John Cage.

John Cage was an early pioneer of computer-based technology as a way to experiment with randomness in sound. His work challenged everything that was then accepted in western music and composition, and he was a prolific writer. Of particular interest is the work titled, perhaps coincidently, Imaginary Landscape No.4 (1951), an improvised performance for 24 musicians and 12 radios – considered the first ever example of electronic music. The creative strategy removes the composer from the final stage of the process but only after a set of creative decisions and limitations have been set, much like Fontcuberta’s strategy with Orogenesis. The limited vocabulary of Cage’s sound corresponds with the limitation of images in Fontcuberta’s work, while both Cage and Fontcuberta experiment the point of deconstruction. Jason Wee points out that Fontcuberta ‘uses one of the oldest scenarios in the conceptualist playbook – submit a plethora of possibilities to a regime of rules and principles, and accept the result’ and shows how Fontcuberta is utilising an established art historical strategy to criticise art history. Interestingly in 1994, Foncuberta was already trying to overlap cartographic data and photography but also sound. In Topophonia: Terrestrial Music, the viewer is asked to manipulate the cartographic data of the mountain of Monserrat to produce images and sound, though it is unclear whether this project was simply a proposal or fully realised either physically or virtually.

It is clear that Joan Fontcuberta’s practice is infused with a desire to question how photographic representation functions in a modern society, and looks to history with the same critical eye. Orogenesis must be seen as a multidisciplinary investigation into the philosophy and politics of, not only, photographic representation but the role of the imaginary and the imagination in all of the disciplines that deal with the representation of space. Patricia Keller when stating that Orogenesis should be read as a way of ‘rethinking the ways in which we read, see, perceive and come into knowledge of the world, offering unique and at times arresting explorations of temporality, history, and perception through art’ as a summary of Fontcuberta’s intentions. But while the work could feel theoretically cumbersome, one must acknowledge how the mischievous spirit of Joan Fontcuberta infiltrates the creative process, responding to dualities and antagonisms with a deadpan humour that ensures that the work is accessible and open to those who view it.

Images ©Joan Fontcuberta

Kay Watson is a researcher, curator and archivist. She currently works in the curatorial department at the Contemporary Art Society and has experience of working on digital and archive projects for The Photographers’ Gallery, Autograph ABP and many private collections. She has specialist knowledge of working with digital and print photographic archives and collections with acquisitions and conservation experience. She has an MA History of Art with Photography (Distinction) from Birkbeck College. Research interests include post-war and contemporary art, photography and digital media practices, institutional histories and representations of gender.

References:

J. Fontcuberta, ‘Interview: J Fontcuberta, Landsapes Without Memory’, Audio Interview, 2010, http:// www.eyecurious.com/interview-joan-fontcuberta-landscapes-without-memory/

J. Wee, ‘Landscape as Exhausted Form: The Non-Site and Joan Fontcuberta’s Landscapes of Landscapes’, Art Papers, 30 (2006), p.25

RE Krauss, ‘The Originality of the Avant-Garde’ in C. Harrison and P. Wood (eds.) Art in Theory 1900 – 2000: An Anthology of Changing Ideas (Oxford, Blackwell Publishing: 2003) p.1033

J. Fontcuberta, ‘Revisiting the Histories of Photography’ in J. Fontcuberta (ed.) Photography: Crisis of History (Barcelona: Actar, 2002) p.13 8 P. Keller, ‘Joan Fontcuberta’s Landscapes – Remapping Photography and the Technological Image’, Journal of Spanish Cultural Studies (12) 2011 p.143

G Batchen, ‘Painting by Numbers’ in J. Fontcuberta (ed.) Landscapes Without Memory (New York: Aperture, 2005) p. 13

J. Fontcuberta, ‘Interview: J Fontcuberta, Landsapes Without Memory’, Audio Interview, 2010, http:// www.eyecurious.com/interview-joan-fontcuberta-landscapes-without-memory/

J. Fontcuberta, ‘Ecotopia: A Virtual Roundtable: Landscape and History’ in J. Lehan (ed.) Ecotopia: The Second ICP Triennial of Photography and Video (Germany, New York: International Centre of Photography & Steidl, 2006) p. 21

M. Schwartz & J. R. Ryan, ‘Introduction: Photography and the Cultural Imagination’ in J. M. Schwartz & J. R. Ryan (eds.) Picturing Place: Photography and the Geographical Imagination (London, New York: I.B. Tauris, 2003) p. 18

J. Fontcuberta, ‘Ecotopia: A Virtual Roundtable: Landscape and History’ in J. Lehan (ed.) Ecotopia: The Second ICP Triennial of Photography and Video (Germany, New York: International Centre of Photography & Steidl, 2006) p21 surveillance‘ and fuels the unease.

M. Rosler, ‘Image Simulations, Computer Manipulations’ in M. Rosler (ed.) Decoys and Disruptions (Mass, The MIT Press, 2004) p.285. M. Foucault, Discipline & Punish (1975), Panopticism, http://foucault.info documents/disciplineAndPunish/foucault.disciplineAndPunish.panOpticism.html

D. Cosgrove, ‘Introduction: Mapping Meaning’ in D. Cosgrove (ed.) Mappings (London: Reaktion Books Ltd, 1999) pp. 1-2 22

Volk, ‘Joan Fontcuberta’ in J. Lehan (ed.) Ecotopia: The Second ICP Triennial of Photography and Video (Germany, New York: International Centre of Photography & Steidl, 2006) p.112

Hart, ‘The Cartographic Uncanny’ in Layla Curtis (Newcastle Upon Tyne & Walsall: Locus+ Publishing Ltd & The New Art Gallery Walsall, 2006) p.46 30 Hart (2006) p.46

J. Fontcuberta, ‘Interview: J Fontcuberta, Landsapes Without Memory’, Audio Interview, 2010, http:// www.eyecurious.com/interview-joan-fontcuberta-landscapes-without-memory/

J. Wee, (2006), p.26 33 J. Cage, Silence: Lectures and Writings (Mass: The M.I.T. Press, 1967) p.59

N. Carroll, ‘Cage and Philosophy’, The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism (52) 1994 p.96

Batchen, ‘Painting by Numbers’ in J. Fontcuberta (ed.) Landscapes Without Memory (New York: Aperture, 2005) pp. 9-13

J. Cage, Silence: Lectures and Writings (Mass: The M.I.T. Press, 1967)

N. Carroll, ‘Cage and Philosophy’, The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism (52) 1994 pp.93-98

D. Cosgrove, ‘Introduction: Mapping Meaning’ in D. Cosgrove (ed.) Mappings (London: Reaktion Books Ltd, 1999) pp. 1-23

Van Gelder & H. Westgeest, Photography Theory in Historical Perspective (Oxford, WileyBlackwell, 2011)

Hargreaves, Talk at The Photographers’ Gallery: ‘Coordinate: Photography and Mapping’, 2011 M. Hart, ‘The Cartographic Uncanny’ in Layla Curtis (Newcastle Upon Tyne & Walsall: Locus+ Publishing Ltd & The New Art Gallery Walsall, 2006) p.46

J. Fontcuberta, ‘Interview: J Fontcuberta, Landsapes Without Memory’, Audio Interview, 2010, http://www.eyecurious.com/interview-joan-fontcuberta-landscapes-without-memory/ J. Fontcuberta, Landscapes Without Memory (New York: Aperture, 2005)

J. Fontcuberta, ‘Joan Fontcuberta: Archive Noise’, Photoworks, 4 (2005) pp.64-69

J. Fontcuberta, ‘Revisiting the Histories of Photography’ in J. Fontcuberta (ed.) Photography: Crisis of History (Barcelona: Actar, 2002) pp.6-17

M. Foucault, Discipline & Punish (1975), Panopticism, http://foucault.info documents/disciplineAndPunish/foucault.disciplineAndPunish.panOpticism.html

Krauss, ‘The Originality of the Avant-Garde’ in C. Harrison and P. Wood (eds.) Art in Theory 1900 – 2000: An Anthology of Changing Ideas (Oxford, Blackwell Publishing: 2003) pp. 1032 – 1037

R. Lippard, The Lure of the Local (New York: The New Press, 1997)

Keller, ‘Joan Fontcuberta’s Landscapes – Remapping Photography and the Technological Image’, Journal of Spanish Cultural Studies (12) 2011 pp.129-153

M. Rosler, ‘Image Simulations, Computer Manipulations’ in M. Rosler (ed.) Decoys and Disruptions (Mass, The MIT Press, 2004) pp. 259 – 317

M. Schwartz & J. R. Ryan, ‘Introduction: Photography and the Cultural Imagination’ in J. M. Schwartz & J. R. Ryan (eds.) Picturing Place: Photography and the Geographical Imagination (London, New York: I.B. Tauris, 2003) pp.1-18

Wallis, E. Earle, C. Phillips & C. Squiers, Ecotopia: The Second ICP Triennial of Photography and Video (Germany, New York: International Centre of Photography & Steidl, 2006)

J. Wee, ‘Landscape as Exhausted Form: The Non-Site and Joan Fontcuberta’s Landscapes of Landscapes’, Art Papers, 30 (2006), pp.25-27 L. Wells, Land Matters: Landscape Photography, Culture and Identity (London, New York: I.B. Tauris 2011)