Review: Nick Waplington/ Alexander McQueen: Working Process @ Tate Britain

Images courtesy of Nick Waplington / Tate Britain

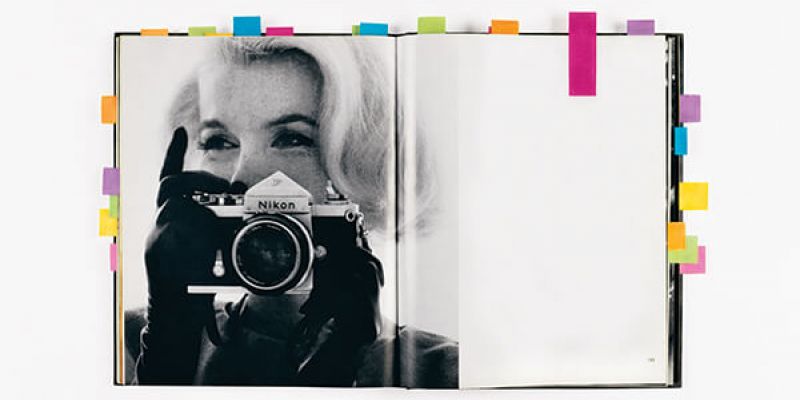

In ‘Working Process’ photographer Nick Waplington gives a rare look behind the scenes of Alexander McQueen’s last collection.

Selected from the previously published book project ‘Working Process’, Waplington’s photographs capture the creative journey of McQueen’s final Autumn/Winter collection ‘Horn of Plenty’ in 2009, one of the most celebrated fashion collections in recent history.

The major exhibition at Tate Britain reveals McQueen’s working practice through a selection of hundred large-scale prints completed by Waplington and McQueen three months before the designer’s suicide.

For over six months Waplington followed McQueen and his team from the designer’s studio in Clerkenwell to the final catwalk show in Paris, documenting every step of the creation of ‘The Horn of Plenty! (Everything But the Kitchen Sink)’, taking on recycling as a guiding theme.

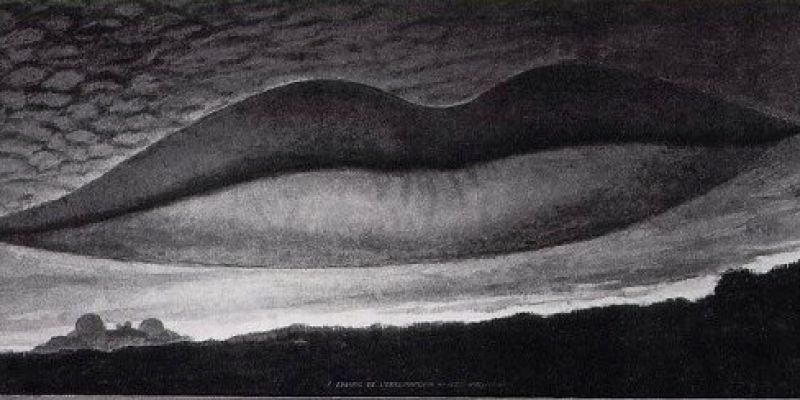

McQueen conceived ‘The Horn of Plenty’ collection as an iconoclastic retrospective of his career in fashion, reusing silhouettes and fabrics from his earlier collections and creating a catwalk set out of broken mirrors.

‘Working Process’ reveals a raw and unpolished side of the fashion world. Waplington juxtaposes candid images of McQueen’s creative process with close-up shots of landfill sites and recycling plants, featuring beer bottles, plastic bags and piles of newspapers.

The exhibition, as the photobook, resulting from this unique artistic collaboration creates a powerful commentary on destruction and creative renewal – themes at the heart of the ‘Horn of Plenty’ collection.

Nick Waplington/ Alexander McQueen: Working Process at Tate Britain until 17 May 2015

Miriam is the Deputy Editor of LPD.

ena Haimes is a freelance arts and culture writer based in London. She studied at Goldsmiths College and the University of the West of England, and contributes to a range of publications as well as writing a visual arts blog.

ena Haimes is a freelance arts and culture writer based in London. She studied at Goldsmiths College and the University of the West of England, and contributes to a range of publications as well as writing a visual arts blog.