Portraiture and Projection by Céline Bodin

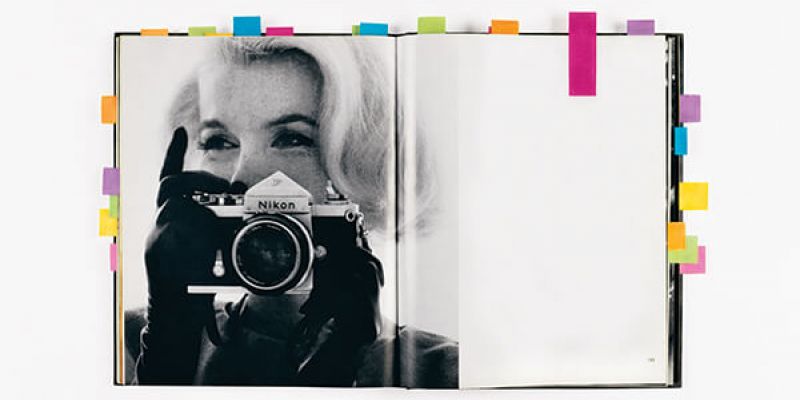

Appearances are bearers of meaning. Our first impressions of a person are concealed within our own imaging process. The tendency to classify into types is almost instinctive; it is a common path towards identification. Portrait photography is its ambiguous medium. Scraping the surface, it destabilises our sense of reality. Because of its supposed guaranty of exact replication of the living reality, it has been established to ‘re-present’ and reveal.

In the 19th century it was considered the best means to classify and identify into types with the use of phrenology and physiognomy, as can be seen in Francis Galton’s composites which merged multiple individuals into one generic image. Photography offers time for the contemplation of subtle details; unlike painting, it isn’t the summary of its subject.

However, along its journey towards contemporary portraiture the notion of representation has become problematic: what is readable only on the surface? To what extent are we learning about the individual portrayed in the instant of an image? Does a portrait truly allow space for genuine presence?

Photography is objective only in its functional aspect but it is somehow weakened in its ability to unite self and subject. Imagery offers fantasy, it can comfort and reassure. Susan Sontag, in her study On Photography (1973), insists on a photograph to be only a ‘narrowly selective transparency’. It is only a part of reality.

The question of projection is key. Posing is an obstacle to the ‘air’ that allows us to recognise the person, as Roland Barthes stated in Camera Lucida (1980). In Portraiture: Facing the Subject, (1997), Joanna Woodall introduces the notion of ‘portraiture’s mimetic mask’, as we are bound to look for the flaw in the surface which will guide us to the true presence. Therefore, the portrait opens itself to interrogation and suggestion more than it delivers a sense of truth or character.

The works of contemporary photographers Rineke Dijkstra, Bettina Von Zwehl, or Marjaana Kella revisit the conventions of portraiture as a genre. Dijkstra’s work is strong in narrative, her subjects enter the camera’s frame to tell a story subtly shaped by the specificity of a moment or action. In the case of Von Zwehl portraiture is treated as a laboratory, as she carries out experiments on her subjects, confronting them with their own vulnerability while the camera witnesses their reaction.

When 19th century French neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot documented hysteria, he proved that the likelihood of the patient performing was increased by the presence of the medical staff. The notion of performance, as an observed state, raises the question of authenticity in the self as it engages with attitude. To disrupt their subjects’ effort at self-representation Von Zwehl, and Dijkstra consider the residual traces of extreme forms of exertion or specific contextual affect, as a bullfighter leaves the arena (Villa Franca di Xira, Portugal, May 8, 1994), a woman just gave birth, or vulnerable subjects lie on the floor holding their breath (Untitled III, No 2, 1999). In Hypnosis (1997-2001), Marjaana Kella scrutinises the suspended moment of her hypnotised subjects (Niclas, Hypnosis, 2001).

Such works invite the viewer to investigate the layers of visibility a subject offers, as the ones represented here face the challenged projection of themselves, necessarily defying the notion of self-consciousness in the moment of being photographed.

The viewer’s examination should therefore remain aware of the body’s performative quality.

Images mediate a cultural coding. Acknowledging this dimension, Cindy Sherman’s work reveals how conventionalised appearances are acted out. (Untitled Film Stills, #12, 1978). Through genre performance she portrays gender as the ‘regulatory model’ Judith Butler defines in Gender Trouble (1990). In Sherman’s self-portraits, gender follows an imitative structure influenced by customs and ideals constantly revaluating the ‘corporealisation’ that imaging should set apart from identification.

Portrait photography can be considered the space for interpretation, its definition relying both on the artist’s intention and its relationship to the viewer’s judgment.

Looking at Thomas Ruff series of passport-like photos our longing to identify is frustrated. The person’s character remains a mystery. The quality of those deadpan portraits remains in the subtle signs of interaction, the way the subjects address the camera.

We can therefore witness multiple layers of projection within a portrait: The photographer interprets the sitter’s self-interpretation, and the sitter in return interprets the photographer and viewer’s expectation. Finally, the viewer interprets the overall impersonation.

In the end, the camera doesn’t classify, we do. As spectators we long to read through the subtlety of a face, the grace of gesture, the drama of expression. Portraits fascinate us because of what they could say. Our relationship with portraiture is therefore a subjective and sentimental one. It is easy to understand that more than it renders personality, photography reveals our intimate projections on the surface. We conjure a dialogue, and the desire to relate might in itself be the only possible truth portraiture could deliver.

Céline Bodin is a French photographer. After studying literature and architecture, she graduated from a photography BA at Gobelins, L’école de l’image in Paris. In 2013 she completed a Photography MA at the London College of Communication. As well as regularly writing about photography, her personal practice explores themes of identity, gender, and the metaphysical frustration of the medium in representation.

ena Haimes is a freelance arts and culture writer based in London. She studied at Goldsmiths College and the University of the West of England, and contributes to a range of publications as well as writing a visual arts blog.

ena Haimes is a freelance arts and culture writer based in London. She studied at Goldsmiths College and the University of the West of England, and contributes to a range of publications as well as writing a visual arts blog.