ESSAY: Man Ray: Surrealism and Photography

While working as a doctor in a military psychiatric hospital during World War I, Frenchman André Breton experienced disturbed soldiers discussing “bizarre images as if they had taken dictation from a genius who had possessed them while reason slept.” In a seemingly parallel universe, one far from the destruction of the war, the art world was turning its back on Dadaism. It had become too academic, too much a part of the bourgeois mainstream it had by definition rebelled against. Dadaism soon morphed into surrealism, spearheaded by Breton and influenced by what he – and the world – had seen during a war that killed sixteen million people. Breton became obsessed with the idea of unconscious autonomy, free association, and the “irrational as the source of creativity and of freedom from any kind of restraint.” In 1924, he wrote the first Surrealist Manifesto. “Completely against the tide… in a violent reaction against the impoverishment and sterility of thought processes that resulted from centuries of rationalism, we turned toward the marvelous and advocated it unconditionally,” he declared, birthing a movement.

Just as the movement’s literature ignored traditional techniques and opted for unstructured, “automatic” writing, as surrealist painters explored illusions and dreams and twisted the idea of everyday normality, photographers scorned the idea that the camera created the final word. They incorporated the primary topics of surrealist focus – dreams, illusions, mystery, eroticism – into photography. By using unconventional techniques, like multiple exposures, solarization, distortion, and montage, these surrealist photographers turned a previously mechanical tool into a medium via which they could express the avant-garde framework of the surrealist movement. The visual language of the camera had been transformed from an instrument of representation to a medium of artistic creation not unlike its supposed “higher-up,” painting.

Few artists exemplified this new photographic structure better than Man Ray. Born in Pennsylvania and raised just outside New York City, he began using the camera as, ironically, a mechanical tool to photograph his paintings and mixed media artworks. In 1921, he moved to Paris and set up a photography studio. There, he met Pablo Picasso and was introduced to Dadaism through another close friend, Tristan Tzara. Man Ray’s process, which he named after himself (Rayographs), involved an already progressive method utilizing objects placed directly on gelatin silver paper to produce an abstracted representation of everyday items. It was only fitting, then, that he’d be swept away by the surrealist movement just a few years later. He had already challenged the notion of photography and the creative, mechanical possibilities of the camera. This would be pushed even further after 1924’s Surrealist Manifesto and the official establishment of such an innovative movement.

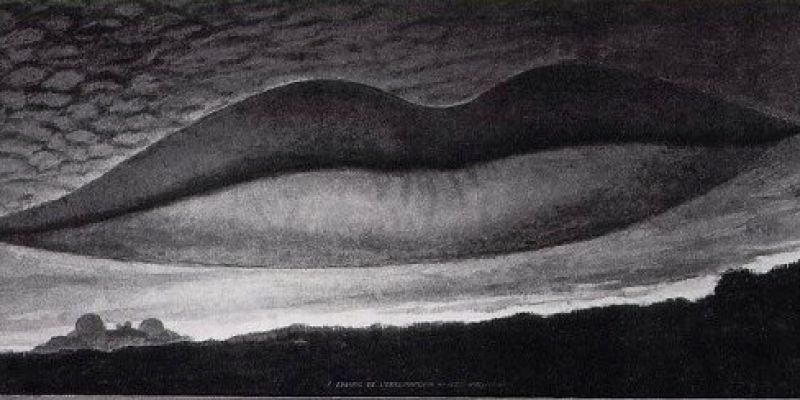

Man Ray’s most famous photographs combined non-traditional photographic techniques with surrealist principles. As a result, he created images that bridge the line between photographs, which were seen as inherently truthful, and otherworldly dreams. For example, in “Observatory Time: The Lovers,” he utilizes a montage technique that combines his own painting with a photograph of his lover, Lee Miller. There is seemingly no context or logic to the image – the female subject is naked and faceless, next to a chessboard; in the sky over a body of water, floats a giant pair of lips. Here, Man Ray truly creates an imaginative, dreamlike world using unconventional photographic processes, combining his own colorless painting with multiple other photos. The resulting work is almost nightmarish and confusing, the woman in a mysterious world entirely unlike our own.

Man Ray confronts the surrealist focus on eroticism more directly with works like “Yesterday, Today, Tomorrow.” Utilizing another non-traditional technique, the image is made up of multiple exposures depicting a nude female with her arms raised over her head. Again, there is an otherworldly element to this image. The face is partly obscured, proportions are distorted, and the solid black background forces the viewer to directly experience the overlapping line and shape of the body; special attention is drawn to the exaggerated breasts and contrasted genitals. The nude form, nearly always female, appears regularly through Man Ray’s and other surrealist works. In his image “The Violin of Ingres,” a nude woman is painted to resemble a violin. Her body, quite plainly, becomes an instrument to be used and played like an object.

Solarization was another experimental technique that frequently appears in Man Ray’s photographs; the photographer would intentionally reverse the light and dark tones on his negatives. In his portraits of, Gertrude Stein, Lee Miller, and Jacqueline Goddard, Man Ray photographs in a very traditional and straightforward style and only later adds a distorting twist to the image through the process of solarization. The surrealist obsession with visions and reveries is also very much a part of these images. The viewer is left entirely alone to determine the circumstance of the photograph. Attempts to unravel details in order to decipher a narrative – the identity of the woman, her thoughts, her mental state – are entirely useless. Man Ray, in line with the other surrealists of his time, had no qualms about potential confusion in the viewer. Surrealism rejected any traditional notion of right or wrong, normality, reality, in use of the camera itself as well as in the images created through it. This was all ignored in favor of alternative photographic methods that assisted Man Ray’s creation of illusions and hallucinations. These, in turn, reflected the movement’s obsession with the subconscious, Freud, and imagination.

The Surrealist community was slowed in the wake of the political turmoil following the Second World War, however, the surrealist movement fully unraveled in 1966 when Breton died. The photography world had all but exploded when surrealism was fading, with the rise of commercial and fashion markets and an increased respect for fine art photography. Yet the avant-garde nature of surrealist photography remained timeless, allowing photographers like Man Ray to publish books, work as a fashion photographer for the likes of Vogue, and be continually exhibited beyond his death in 1976. His lifetime body of work displays a combination of experimental techniques and overarching surrealist principles, making him a chief contributor to both photography as an artistic medium and the surrealist movement. Breton had said surrealism was complete nonconformity. “The marvelous is always beautiful, anything marvelous is beautiful, in fact only the marvelous is beautiful,” he wrote in 1924. It was a fitting statement for a movement that utilized photography as an art form in a way that had never been done before, creating nonrepresentational images of dreams and nightmares.

Meghan Garven is a second year student at the School of Visual Arts, studying photography with honors. She is a freelance photographer who also works part-time at Sasha Wolf Gallery and her research interests include Fauvism and Modernist photography.

Meghan Garven is a second year student at the School of Visual Arts, studying photography with honors. She is a freelance photographer who also works part-time at Sasha Wolf Gallery and her research interests include Fauvism and Modernist photography.